ON MAY 02, 2025 / BY EDITORS GEORGE DAVEY & SHIBRA KHAN

Every year, The Brunel Writer Prize is awarded to the student with the highest graded article submission for the Creative Industries module on Brunel University’s Creative Writing Programme. Rowan Reddington was a runner-up for The Brunel Writer Prize 2025 with his satirical analysis of the economics of being a poet in the 21st century.

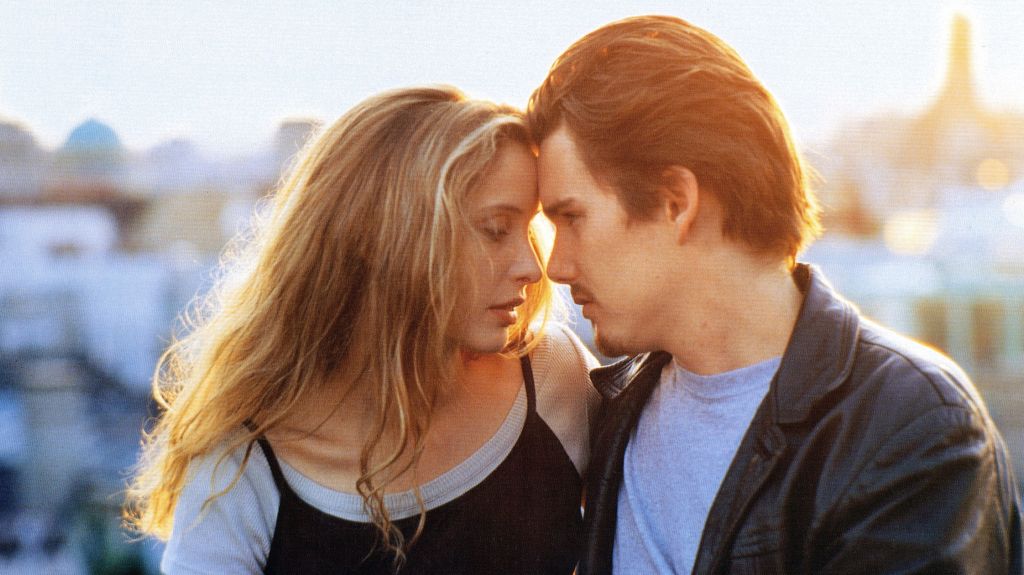

The typical weeknight meal of a working poet.

I.

NO.*

II.

*Not unless you

do a Walt Whitman:

eat beans in a shed,

bin-dive for bread.

(Tricky since Aldi

began to lock the lids.

Don’t ask how the poet

knows about this…)

III. Switching to prose (-poetry?) for the deep dive…

The conventional answer is ‘Sorry, kid. Step away from the quill.’ You can eat, write, and rhyme… just not all three at once. It’s tough enough being a novelist. And people read novels.

This bleak prognosis is usually served with the caveat that writers need day jobs, side hustles, or rich benefactors (like an entrenched class system!). It won’t be long till you hear the c-word flying about.

Copywriting.

Because you honed your ear and eye and heart in order to line shareholders’ pockets, right? Because the primary role of the poet is to ease consumers’ suspicions that the annihilation of the living earth won’t be allayed by Fanta bottles being made from 80% recycled plastic… and the secondary role of the poet is to persuade the people on the escalators at Liverpool St. station that BAE systems are a cosy, family business not the stonehearted beneficiaries of industrial murder, yeah?

‘OK. So… not a fan of copywriting, then,’ says the bemused, well-meaning, but essentially disapproving distant relative/beleaguered colleague/long-suffering friend that you’ve cornered or been cornered by at some imaginary social function. (An optimistically early-season BBQ, let’s say).

The next unsolicited piece of advice, posing as a question and accompanied by aerial chunks of charred chipolata, that will leave this person’s mouth (once they’re done glancing furtively up at that dark, blimp-like raincloud on the horizon) will be: ‘You could be an Instapoet?’

You go to speak but they cut you off.

‘No wait, let me guess,’ they say, between glugs of warm cider (your second cousin was right: your great-uncle does have a drinking problem). ‘Peddling paper-thin platitudes that pander to the misanthropic tech conglomerates’ commodification of our very minds, via that euphemistically-named techno-succubus, the “attention economy”… that’s not poetry, either. Is it?’

Touché, Len! you want to shout.

But ‘cause you’re a deep and unfathomable Artist, you say: ‘Actually, I like Rupi Kaur. It’s not her fault I get stuck watching cat videos. And no one gets into Eliot first—’ dramatic pause as the first raindrops splatter off Len’s former-county-hockey-player nose. ‘Maybe, Len, milk and honey are gateway drugs?’

You’re pleased with that piece of dialogue. You make a mental note.

‘What?’ says Len, sheltering beneath an untouched platter of homemade coleslaw.

In my humble opinion, you’ve both got a point. On the one hand, it’s true that Instapoets may have saved poetry: the meteoric rise of poets like Kaur has coincided with a significant bump in sales. On the other, social media poetry must be get-able on first encounter. A recipe for vapid verse if there ever was one.

(𝚛𝚎𝚌𝚒𝚙𝚎 𝚏𝚘𝚛 𝚟𝚊𝚙𝚒𝚍 𝚟𝚎𝚛𝚜𝚎

𝟷 x 𝚜𝚎𝚕𝚏-𝚑𝚎𝚕𝚙 𝚙𝚕𝚊𝚝𝚒𝚝𝚞𝚍𝚎

𝟷 x 𝚛𝚎𝚏𝚎𝚛𝚎𝚗𝚌𝚎 𝚝𝚘 𝚏𝚕𝚘𝚠𝚎𝚛𝚜/𝚛𝚊𝚒𝚗

𝟷 x 𝚛𝚎𝚏𝚎𝚛𝚎𝚗𝚌𝚎 𝚝𝚘 𝚎𝚡

𝚕𝚒𝚖𝚙𝚕𝚢 𝚜𝚑𝚊𝚔𝚎

𝚐𝚊𝚛𝚗𝚒𝚜𝚑 𝚒𝚗 𝚙𝚞𝚗𝚌𝚝𝚞𝚊𝚝𝚒𝚘𝚗-𝚕𝚎𝚜𝚜 𝚕𝚘𝚠𝚎𝚛𝚌𝚊𝚜𝚎 𝚠/𝚜𝚑𝚊𝚔𝚢 𝚕𝚒𝚗𝚎 𝚍𝚛𝚊𝚠𝚒𝚗𝚐

𝚜𝚎𝚛𝚟𝚎 𝚌𝚘𝚕𝚍)

Anyway, getting back to what this article is ostensibly about, to get paid as an Instapoet you apparently had to be there early on. The best we can hope for now is some kind of trickledown poetic renaissance.

But probably the Lens of this world are right: it’s day jobs for the foreseeable. We’ll need to keep weighing our good coffee and fancy boxes of herbal tea as loose carrots at the self-service kiosk for a while yet, won’t we, poets?

Rowan is a poet and tree surgeon living in East London. His most recent publication is the short story ‘Beat Phase’, featured in the New Adult anthology ‘It’s Fine, I’m Fine’ (edited by Kat Gynn). It tells the story of a verbose and naive Ginsberg-fanatic’s move to London, that ‘cobbled, storied morgue where you can’t even yawn without swallowing ghosts’, and the subsequent anticlimax known as “adult life”.